The World Cup in Qatar has brought sportswashing to the front of public mind yet again.

The process by which corporations, nations or groups use sport to repair their public image. But sportswashing is not a new concept specific to Qatar, the World Cup, or even football.

To unpack why sportswashing is effective it’s worth thinking about what sport represents. Whether it’s an individual athlete whose determination inspires us to fight against adversity, or a team effort that makes us believe in the power of collaboration, sport garners so much respect because it showcases people who have dedicated themselves to achieving excellence. As a result, it makes sense for any nation state to attach itself to sport because close proximity to principles like determination, collaboration and fair play is great PR for any regime.

Historically, sport has framed the identity of civilisations for centuries. Ancient Greece is defined by philosophy and the Olympics, courtesy of the Athenians. Roman civilisation is remembered for gladiatorial combat. Wrestling is a frequent feature of literature on pre-colonial West Africa. Throughout history, civilisations have been characterised by the prominent sports of the time. Qatar declared independence from the British in 1971 and for a country that wants to establish itself as a global player, historical precedence would naturally lead them towards the world’s biggest sporting event: the FIFA World Cup.

"FIFA’s growth post-WW2 has made hosting the World Cup a key target for regimes trying to establish themselves on the global stage."

A nation using sport to define itself sounds innocent enough. The danger comes when the international community acknowledges a desire for global recognition, but is blind to what specific regimes stand for. This is exactly what happened when the 1936 Olympics took place in Nazi Germany under the rule of Adolf Hitler. If anyone believes that hosting an international sports competition makes a regime respectable, this example alone disproves that. Jesse Owens, a Black American sprinter, famously won the 100m in front of Hitler in 1936. But Owens' victory didn’t dispel the myth of Aryan superiority in Germany. A German foreign office official instead claimed that his victory was inevitable because he was essentially an animal. Unfortunately, the PR spin was effective enough for the international community to legitimise Hitler for another three years. The England football team even travelled to Germany for a friendly match and performed a Nazi salute in 1938.

Netflix’s recent documentary ‘FIFA Uncovered’ highlights that FIFA’s growth post-WW2 has made hosting the World Cup a key target for regimes trying to establish themselves on the global stage. The 1978 World Cup took place in Argentina, two years after the country was taken over by a military junta led by Jorge Rafael Videla. They were responsible for the torturing of dissidents and killing an estimated 9,000 people during the “National Reorganisation Process”. When we think of the 1978 World Cup in Argentina, our memories are rich with a triumphant victory on home soil for the Argentines. But their 3-1 win over Holland at the Estadio Monumental was less than a mile away from a torture prison that claimed thousands of lives. It is reported that prisoners could actually hear the crowds roar as they were being beaten to death. This is the danger of sportswashing. On the world stage Argentina’s footballing prowess supersedes their reputation for atrocities. A quick Google search of “Argentina 1978” brings up results of the World Cup, not thousands of people being butchered by a dictatorship. Football should not be used to sanitise crimes against humanity – but it has been.

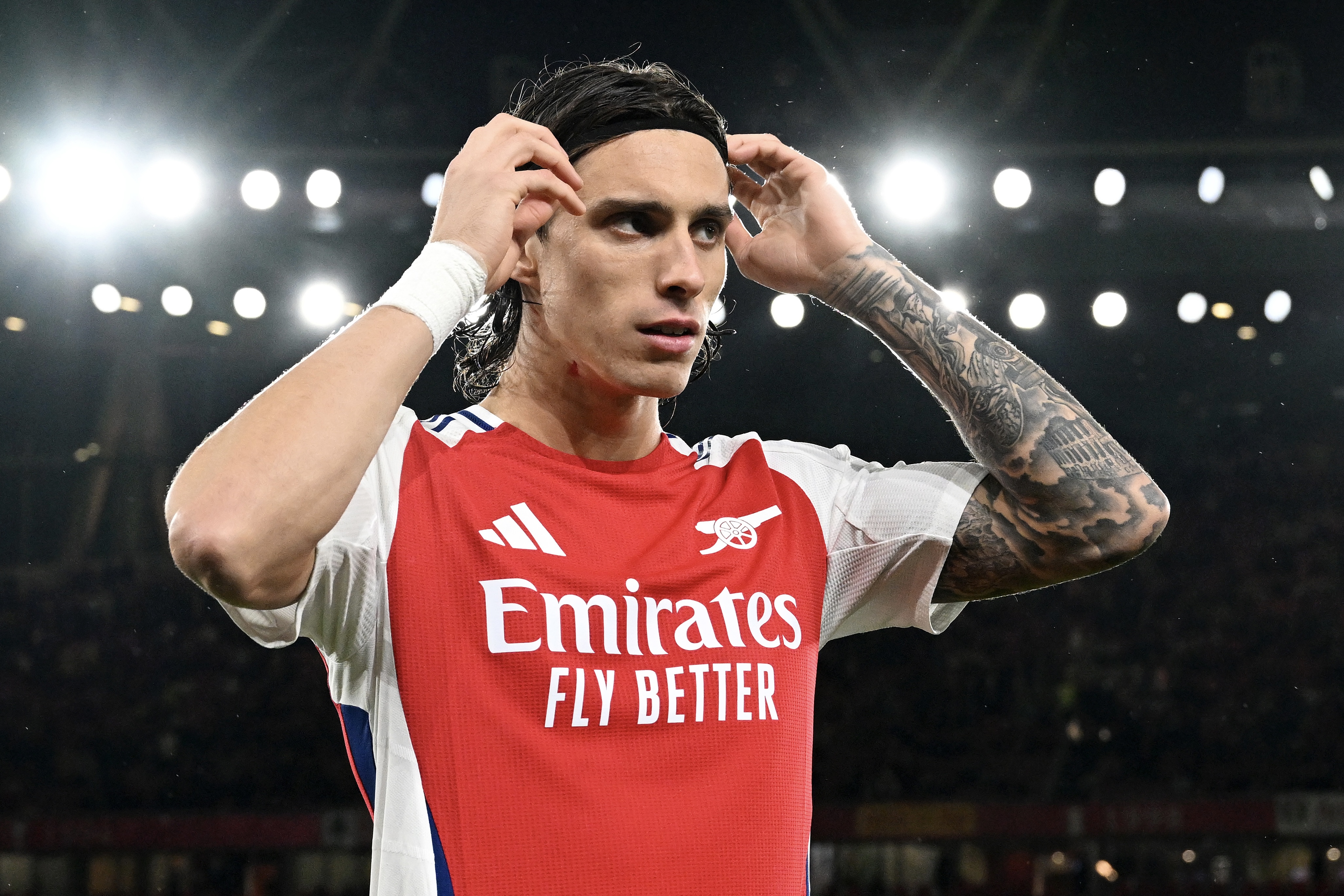

The global appeal of European leagues – most notably the Premier League – means that states don’t even need to host a World Cup to sanitise their image by virtue of alignment to football anymore. Top European clubs are recognisable the world over. Manchester City, PSG and Newcastle United are now all owned by Gulf states. There is legitimate concern that criticisms of Gulf state ownership is rooted in Islamaphobia and xenophobia – and sometimes this is the case. Especially when ownership by U.S. conglomerates like FSG, who own Liverpool (for now), don’t seem to be questioned in the same way.

One could argue that private ownership of football clubs (as opposed to a fan ownership model like the Bundesliga’s 50+1 rule) doesn’t prioritise fan satisfaction. The difference is that a nation state owning a football club is not the same thing as a private company, from a nation state, owning a football club. A private company like FSG operating within a democracy is not a representative of the United States government in the same way that Sheikh Mansour is a representative of the UAE as Deputy Prime Minister. This has consequences at a domestic and geopolitical level.

Earlier this year, The Guardian reported that Sheikh Mansour was able to buy lucrative Manchester land at a fraction of its value for property developments. This was through a “Manchester Life'' deal between Sheikh Mansour and Manchester City Council. At the time of the reported £1bn sale Mansour already owned Manchester City, whose Etihad Stadium is nearby. Local recreational activities like elite football are a great selling point for property development bids. Meanwhile affordable housing is one of the key political issues facing Britain. Between 2016 and 2018, Manchester City Council granted planning permission for 14,667 homes in big developments. How many of them were deemed “affordable” by planning documents? 0. So despite affordable housing being one of the issues shaping modern Britain, someone was able to build thousands of unaffordable properties aided by the connections that came with owning Manchester City.

On an international scale, sanctions are one of the few tools governments have before all out war. The sanctions of Russian oligarchs saw Roman Abramovich vacate his ownership of Chelsea earlier this year. If our government entered conflict with a state that owns a high profile club, said nation could destabilise the lives of people attached to the club very easily. Staff could immediately be without jobs and local economies quickly jeopardised.

As such, sportswashing goes beyond just cleaning up a nation’s reputation. When unchallenged long term, it acts as a political strategy which allows perpetrators to act with total impunity.

.svg)

%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%202.jpg)

%20copy-2.jpg)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)