Watch a Champions League game from the 90s and you’re almost guaranteed to see a glint of silver round someone’s neck.

Crucifixes fighting to be liberated from polyester, shark teeth angling for a second in the spotlight, bejewelled monograms bouncing briefly free of a chasing defender’s collar. Kluivert, Figo, Nedved, Baggio, Wright. Mavericks of the game that all chose to add that extra flash of brilliance to their on-pitch fit. Religious, superstitious or simply sartorial, chains were expressions of a player’s inner feeling, of how they really were as people. Then, suddenly, in 1999, they were gone: victims of a malicious force at play.

It didn’t start with football. This malicious force had tendrils everywhere. Take the cinema for example. You know how it seems like every film they put out now is a remake? Or a sequel? Or a weirdly convoluted extension of an existing cinematic universe? There’s a reason that’s happening. Since the turn of the century, a process of steady commercialisation has taken over the arts and culture industries. Art, Music, TV, Film, Video Games – mediums of expression that are now worth billions because investors saw opportunities to make money.

In principle, investment in the arts certainly isn’t a bad thing: more money for more people to make more things, right? Except these investors don’t provide millions in funding just because they want to support creators – they do it to make a profit. Why wouldn’t they? They’re investors, that’s their job. The difficulty with banking on the arts, though, is that sometimes people don’t like the art produced. People don’t like it, won’t pay money to consume it, and the return on the original investment dwindles.

In order to combat this conundrum, those with the chequebooks came up with a cunning plan. They now only invest in things they know will make money. Sure-bets only. Hence the masses and masses of prequels and sequels. A study by Adam Mastroianni shows that in the year 2000, the percentage of top 20 grossing films that were part of an existing universe was about 25%. Last year, it was over 90%.

Instead of encouraging creators to take risks, tell new stories and try new things, those in control want rules and regulations.

The same thing is happening in football. As much as they claim otherwise, Todd Boehly and the Premier League’s other billionaire owners haven’t invested in European football because they love the game. Boehly and Clearlake Capital didn’t pay £4.25bn for Chelsea because they were big Gavin Peacock fans growing up. They’re here to make money and, in their eyes, the best way to do that is to make the game as risk free as possible.

We’ve already seen their attempts to take the uncertainty out of football. VAR wasn’t implemented for the sake of fans in the stadium – it’s there so owners don’t lose millions in prize money based on a refereeing mistake. The European Super League tried to eliminate the risk of relegation and with it the huge potential loss in revenue. FFP doesn’t work because those who would be penalised by it don’t want it to work. How would an effective financial regulator aid their profits?

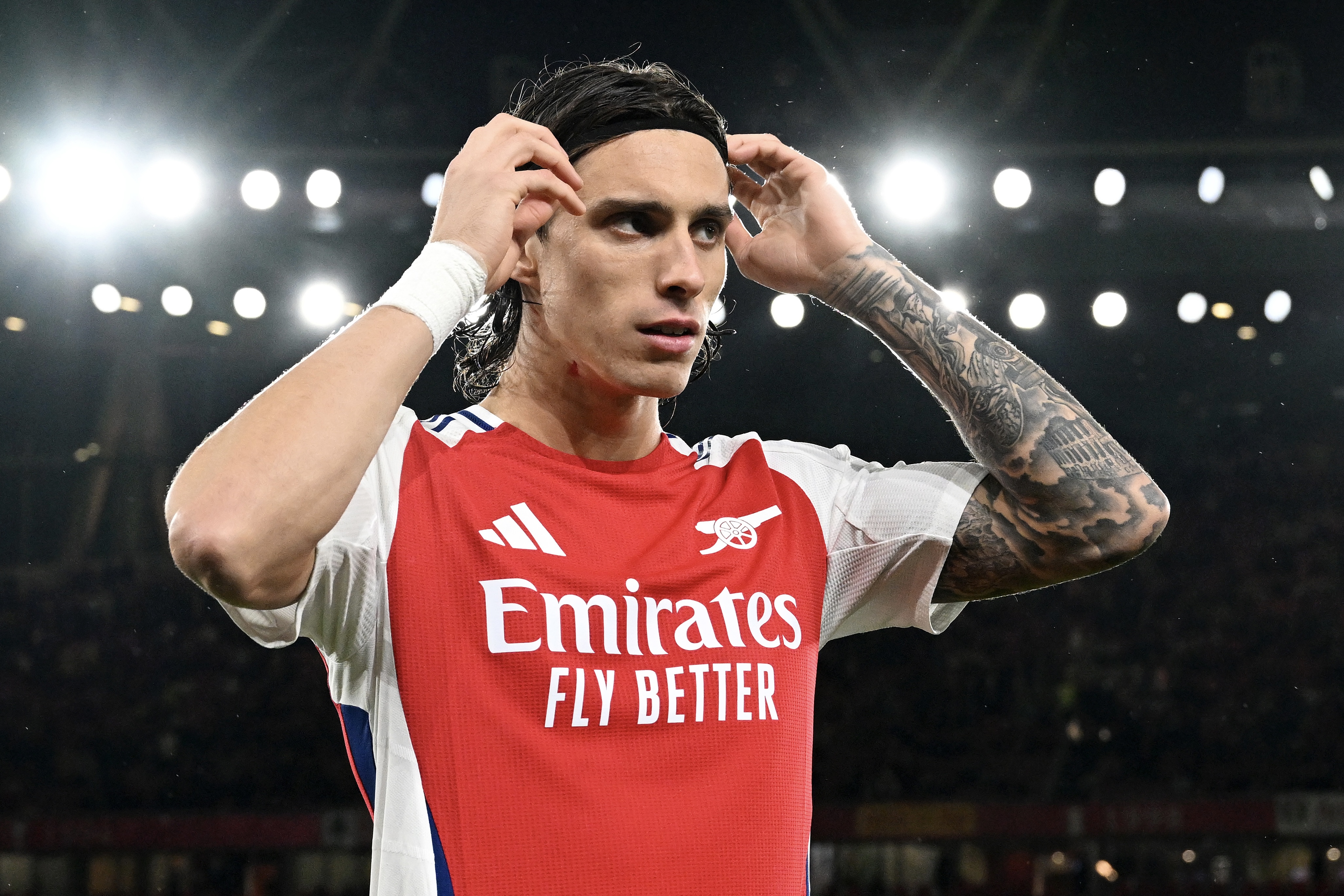

It’s not only at board level that risk-taking is discouraged, either. Investors don’t want their billions to be jeopardised by a player stepping out of line. Compared to other major sports, football players are heavily restricted in how they express themselves on and off the pitch. Take Allan Saint-Maximin as a prime example. Banned from wearing his favourite headband by some chino-wearing bureaucrat who thinks the LV represents general insurance. How about Paul Mullin at Wrexham? Prevented from making a political statement on his boots by the same club who welcomed Victorian ghoul Jacob Rees-Mogg a couple of months earlier. Let’s not even start on Dominic Calvert-Lewin: perpetually slated on social media just for expressing himself outside of the acceptable tattoos and haircut sport-fashion paradigm. 'Stick to football', they’re told. 'Keep quiet, play the game, don’t disrupt the bottom line'.

The issue is, football isn’t made great by people toeing the line. Fans don’t fall in love with conformists, and they don’t tell tales of a five yard pass. The game is made beautiful by risk-takers, players willing to express themselves in unexpected ways. That's why I have a plea for football’s powers that be: let them wear chains.

The chain represents a move towards individuality. In an environment where players are literally required to dress identically, not to mention the enormous societal pressure for them to look and act a particular way, we should celebrate when they take an opportunity to express their own personality. Also, thinking purely aesthetically for a second, do footballers not just look sick when they wear chains? It brings a personal flavour to a strict uniform. How many times have you seen Instagram moodboard accounts repost that photo of Maldini with a gold ropelink popping out?

They're currently outlawed due to safety – but is wearing a necklace when playing football actually that dangerous? Jewellery is officially permitted in the NFL, a far more physical game, as well as in professional baseball, cricket, tennis, golf and more. Lewis Hamilton openly flaunted F1’s ban on jewellery, describing it as “a step backwards”. Regardless, can anyone remember an injury sustained by a player in the (famously gentile) football matches of the 80s and 90s as a result of wearing a chain? Footballers should be allowed this small window to express themselves.

Boehly, Agenlli, Perez and co are on a mission to sterilise our game. They won’t stop until every bump in football’s face has been smoothed out, every interesting quirk standardised into a packagable, saleable commodity. We must fight to maintain football’s small eccentricities and to reclaim some which have already been erased. Admittedly, within the wider context of football’s commercialisation, the chain is a small thing. But isn’t that more reason to do it? A small step towards old excitements. Let them wear chains. Run the jewels.

.svg)

%20copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%202.jpg)

%20copy-2.jpg)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)